dissuade others from doing them harm in cyberspace? In the words of former Estonian President Toomas Ilves, “The biggest problem in cyber remains deterrence. We have been talking about the need to deal with it within NATO for years now.”1

Since the turn of this century, the Internet has become a general purpose technology that contributed some $4 trillion to the world economy in 2016 and connects nearly half the world’s population. In contrast, a mere twenty years ago, there were only 16 million Internet users, or one-half percent of the world’s population. Cross-border data traffic increased by a factor of forty-five times in the past decade alone. Power and interdependence go together, however, and burgeoning dependence on the Internet has been accompanied by a growing vulnerability that has created a new dimension of international insecurity. More than 20 billion devices are forecast to be connected to the “Internet of Things” in the next ªve years, and some analysts foresee such hyperconnectivity enormously expanding the range of targets for cyberattack.Conclusion The answer to the question of whether deterrence works in cyberspace is “it depends on how, who, and what.” Table 1 summarizes some of the major relationships described above. In short, ambiguities of attribution and the diversity of adversaries do not make deterrence and dissuasion impossible in cyberspace, but punishment occupies a lesser degree of the strategy space than in the case of nuclear weapons. Punishment is possible against both states and criminals, but attribution problems often slow and blunt its deterrent effects. Denial plays a larger role in dealing with nonstate actors than with major states whose intelligence services can formulate an advanced persistent threat. With time and effort, a major military or intelligence agency is likely to penetrate most defenses, but the combination of threat of punishment plus effective defense can inºuence calculations of costs and beneªts.

The United States has become increasingly dependent on cyberspace for the flow of goods and services; support for critical infrastructure such as electricity, water, banking, communication, and transportation; and the command and control of military systems. At the same time, the amount of malicious activity in cyberspace by nation-states and highly capable nonstate actors has increased. Paradoxically, the fact that the United States was at the forefront of the development of cyber technology and the Internet made it disproportionately vulnerable to damage by cyber instruments. As recently as 2007, malicious cyber activities did not register on the director of national intelligence’s list of major threats to national security. In 2015 they ranked first

Conclusion

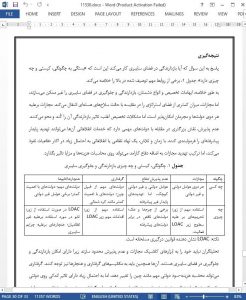

The answer to the question of whether deterrence works in cyberspace is “it depends on how, who, and what.” Table 1 summarizes some of the major relationships described above.

In short, ambiguities of attribution and the diversity of adversaries do not make deterrence and dissuasion impossible in cyberspace, but punishment occupies a lesser degree of the strategy space than in the case of nuclear weapons. Punishment is possible against both states and criminals, but attribution problems often slow and blunt its deterrent effects. Denial plays a larger role in dealing with nonstate actors than with major states whose intelligence services can formulate an advanced persistent threat. With time and effort, a major military or intelligence agency is likely to penetrate most defenses, but the combination of threat of punishment plus effective defense can inºuence calculations of costs and beneªts.