Abstract

We attempt to advance the existing narrative about the role of local institutions vis-à-vis the organizational capabilities of Chinese SMEs, and the influence of such linkages on the innovation capability of these firms. Specifically, we complement recent work by investigating the impact of macro- as well as micro-level aspects of Chinese institutions (Government support; Guanxi) on the ‘Improvisation’ and ‘Learning’ capabilities of Chinese SMEs and, ultimately, these firms’ innovation capability. Our conceptual arguments are embedded in Institutional, Organizational learning, and Resource-based theories. We isolate, unpack, and discuss several inter-related, yet distinct, causal mechanisms that ultimately influence Chinese SMEs’ innovation capability development. Based on a Partial Least Squares analysis of more than 200 firms, we find empirical support for all six hypotheses which represent the above-mentioned relationships. Our findings offer insights pertaining to: (1) the relative impact of institutional versus firm-specific factors in developing organizational proficiencies, (2) the mapping of macro- and micro-level institutional effects on organizational proficiencies, and (3) the relative effect of organizational proficiencies on innovation performance.

1. Introduction

In China, as in many other parts of the world, small and medium sized enterprises (SMEs) are an integral part of the domestic economy (Cardoza, Fornes, Li, Xu, & Xu, 2015; Chen, 2006). In fact, Wang and Yao (2002): 199) refer to them as the “…backbone of China’s economic growth.” Recent reports indicate Chinese SMEs (henceforth, CSMEs) account for approximately 60% of China’s GDP (China Daily, 2017), more than 70% of patents (China Banking News, 2018), and nearly 70% of exports (Ecovis, 2017) with an export-growth rate higher than that for overall exports (Zhang, Wang, Zhao, & Zhang, 2017). Not only do CSMEs contribute in economic terms, i.e., GDP, tax revenues, and employment (China Banking News, 2018), these firms are also strategically crucial—as ‘innovation’ engines that augment China’s economic and social development (e.g., Cardoza et al., 2015). However, with rapidly changing technology and market environments, CSMEs face intense global competition. Consequently, many CSMEs must transition from competing primarily on price to competing via developing innovative products that offer the best total value to their customers (Loon & Chik, 2019).

5. Discussion and conclusions

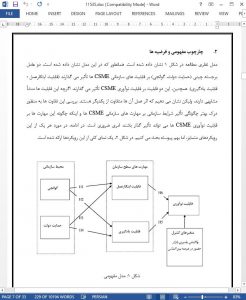

Our findings offer at least three interesting insights about factors that augment CSMEs’ innovation capability. One, despite ample conventional wisdom about the substantial favorable effects of local Chinese institutions (here, personal connections and perceptions of government backing to domestic firms), Guanxi and Government Support collectively explained merely 10% to 15% of the variance in relation to firms’ improvisation and learning capabilities (refer to the two ovals in Fig. 3). This suggests that other factors—likely firm-specific factors (Petti et al., 2017)—play a more important role in developing these capabilities. Such a conjecture should not imply that the above-mentioned institutional-level variables are unimportant; they are not. Rather, it is conceivable that Guanxi and perceptions of Government Support play a crucial role in capability development in the early stages of such development cycles. After such an initial seeding, firm-specific considerations would amplify CSMEs’ capability development processes. Stated differently, CSMEs ought not to view Guanxi and/or Government Support as omnipotent causal influences. Instead, our findings suggest these influences only be viewed as important catalysts for developing CSMEs’ capability platforms. Thus, CSMEs ought to step away from an exaggerated and deceptive sense of security arising from personal connections and (perceived) government support. Instead, CSMEs should focus on firm-level engines for developing their longterm innovation prowess.