Abstract

Frequent drying of ponded water, and support of unique, highly specialized assemblages of often rare species, characterize temporary wetlands, such as vernal pools, gilgais, and prairie potholes. As small aquatic features embedded in a terrestrial landscape, temporary wetlands enhance biodiversity and provide aesthetic, biogeochemical, and hydrologic functions. Challenges to conserving temporary wetlands include the need to: (1) integrate freshwater and terrestrial biodiversity priorities; (2) conserve entire ‘pondscapes’ defined by connections to other aquatic and terrestrial systems; (3) maintain natural heterogeneity in environmental gradients across and within wetlands, especially gradients in hydroperiod; (4) address economic impact on landowners and developers; (5) act without complete inventories of these wetlands; and (6) work within limited or non-existent regulatory protections. Because temporary wetlands function as integral landscape components, not singly as isolated entities, their cumulative loss is ecologically detrimental yet not currently part of the conservation calculus. We highlight approaches that use strategies for conserving temporary wetlands in increasingly human-dominated landscapes that integrate top-down management and bottom-up collaborative approaches. Diverse conservation activities (including education, inventory, protection, sustainable management, and restoration) that reduce landowner and manager costs while achieving desired ecological objectives will have the greatest probability of success in meeting conservation goals.

1. What are temporary wetlands?

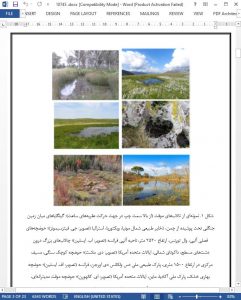

Intermittently inundated wetlands, known as temporary wetlands, are generally shallow, small, aquatic features found in a variety of landscape settings. Temporary wetlands vary greatly in their predominant water sources and outflows, and in all cases are connected to other aquatic features through atmospheric connections inherent to the water cycle (Mushet et al., 2014). Their key defining feature is that they often dry annually or unpredictably to the point that they lack ponded surface water. The drying of temporary wetlands results in shorter hydroperiods (i.e., the length of time water is ponded and frequency of flooding) relative to permanent aquatic systems. Hydroperiod is the main driver of communities and population dynamics (Boix and Batzer, 2016) and leads to these wetlands often supporting unique biotic communities (Wiggins et al., 1980; Williams, 1985). Examples of small temporary wetlands include cypress domes, vernal pools, bays, prairie potholes, playas, athalossohaline (saline endorheic) wetlands, springsoaks, gilgais, ponds from lowland to alpine environments, Mediterranean ponds, turloughs and rock pools; and, although they are mainly small in size, globally they cover a greater total area than lakes (Fig. 1; Downing et al., 2006).

5. Conclusion

The biodiversity, hydrological and biogeochemical functioning of temporary wetlands that support ecosystem services, and their important social value in different countries, make these small natural features of considerable interest to practitioners and scientists alike. Meso-filter approaches focus on conserving small natural features in a human-dominated landscapes at a scale that engages landowners while effecting conservation at scales relevant to supporting ecosystem processes. Restoring a single temporary wetland in a degraded surrounding environment is often irrelevant and ineffective. A holistic approach to developing flexible conservation strategies will have the greatest probability of success in maintaining more fully functioning landscapes.