Abstract

Relying on the Stambaugh, Yu, and Yuan (2015) mispricing score and on 45 countries between 1994 and 2013, I document economically meaningful and statistically significant cross-sectional stock return predictability around the globe. In contrast to the widely held belief, mispricing associated with the 11 long/short anomalies underlying the composite ranking measure appears to be at least as prevalent in developed markets as in emerging markets. Additional support for this conjecture is obtained, among others, from tests for biased expectations based on the behavior of anomaly spreads surrounding earnings announcements as well as from within-country variation in development.

1. Introduction

In their marketing materials, mutual fund companies often claim that emerging markets yield better opportunities for stock picking than developed markets.1 However, the evidence is mixed. Dyck, Lins, and Pomorski (2013) and Huij and Post (2011) indeed find that active management outperforms passive management in emerging markets or is at least successful enough to cover its expenses. In contrast, Busse, Goyal, and Wahal (2014), Eling and Faust (2010), Ferreira, Keswani, Miguel, and Ramos (2013), or Kang, Nielsen, and Fachinotti (2011) report that mutual funds tend to underperform traditional benchmarks, and find little to no evidence for stock picking skill, superior performance, or performance persistence in emerging markets.

6. Conclusion

Based on the Stambaugh, Yu, and Yuan (2015) mispricing score, a comprehensive international data set, and conceptually diverse tests, my findings cast doubt on the notion that the markets outside of the most developed ones are necessarily less efficient.

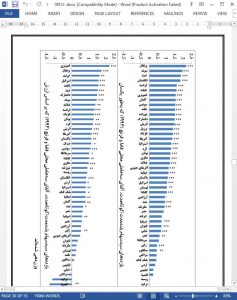

These findings suggest several directions for further research. First, there could be forms of mispricing that are not reflected in the Stambaugh, Yu, and Yuan (2015) score and that are particularly strong in emerging markets. Relatedly, the composite mispricing measure is based on public information only, and thus does not speak to the strong form of market efficiency. Second, the measure is purely cross-sectional and thus does not allow to draw inferences about market-wide overpricing or underpricing. Third, most of the large cross-country variation in return predictability, as indicated in Fig. 1, is currently unexplained. Fourth, it is an open question as to what extent institutional investors’ sentiment-induced demand shocks, investment constraints, or agency conflicts in the sense of DeVault, Sias, and Starks (2015), Edelen, Ince, and Kadlec (2016), or Lakonishok, Shleifer, and Vishny (1994) contribute to mispricing in developed markets.