Abstract

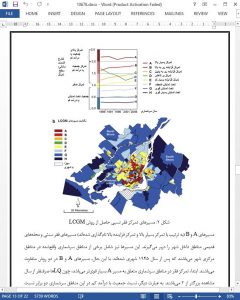

Longitudinal analysis is rarely leveraged in the field of geography to understand neighbourhood change despite many studies documenting important transformations within metropolitan areas (e.g. gentrification, impoverishment of inner suburbs, etc.). This paper aims to identify and model trajectories of neighbourhood poverty in Montreal over five consecutive census years (1986, 1991, 1996, 2001 and 2006), using Latent Class Growth Modelling. Neighbourhoods are classified in eight groups, identifying those with stable, increasing or declining trajectories of poverty. Multinomial logistic regression analysis shows that the proportion of residents with low levels of education, unemployment rate, proportion of recent immigrants and the proportion of renters measured at the beginning of the period (1986) are important predictors of poverty trajectories, as are variations throughout the study period (1986–2006) in the proportions of recent immigrants and of residents with low levels of education.

Introduction

Globalization, economic restructuring, demographic shifts, as well as changes in government policies have modified the social divisions of cities (Jargowsky, 2003; Van Kempen & Murie, 2009; Walk, 2001), notably the spatial distribution of low-income populations within metropolitan areas. As a result, the geography of poverty and social deprivation is now receiving growing attention in North America as well as in Europe (Cooke & Marchant, 2006; Heisz & McLeod, 2004; Kearns & Parkinson, 2001; Kitchen & Williams, 2009; Lupton & Power, 2004; Madden, 2003a, 2003b). To date, most of the empirical work on neighbourhood change has examined transformations between two points in time (Kitchen & Williams, 2009; Mikelbank, 2006; Reibel & Regelson, 2011; Vicino, 2008). With the exception of the recent work of Mikelbank (2011) on the ClevelandeAkron metropolitan area, few studies have analyzed trajectories with precision i.e. they have not investigated changes in the socioeconomic characteristics of neighbourhood populations over more than two points in time.

Conclusion

Our results show that radical changes in the geography of poverty are an exception in the Montreal CMA. Poverty zones evolved according to their initial characteristics and changes were minor over time, except for CTs in the gentrification trajectory where changes in poverty levels were more marked. From 1986 onward, we observed the presence of weak and very weak concentrations of low-income populations in the older suburbs, as indicated by LQ values greater than one. This illustrates that the impoverishment process was already underway in these CTs and that it slightly increased during the period of study (these CTs were characterized by trajectories of increasing poverty). Although census tracts in trajectories F and G were characterized by low LQ values, indicating lower poverty in these neighbourhoods than across the Montreal CMA, poor populations were nonetheless present within these territories. As documented in past studies (Séguin, 1998; Séguin & Germain, 2000), this supports the phenomenon of a relative social mix in Montreal neighbourhoods, even in wealthier areas.