Abstract

Contemporary computer and networking technologies have expanded the scope and scale of deceptions worldwide. Among hackers, security practitioners, and other technologists, ruses designed to gain access to otherwise secure information or computer systems are often referred to as “social engineering.” To date, little research has explored the creation of fabrications from the perspective of social engineers. The current study addresses this gap by examining the attributes that social engineers ascribe to successful and effective social engineering deceptions through a grounded theory analysis of interviews with social engineers (n = 37). Results reveal twelve characteristics of effective social engineers according to participants–findings which indicate that perpetrators consider social context, assumptions about human nature, the complexities of social networks, the role of social conventions, and the limitations of human processing and reasoning in the execution of their deceptions. The study concludes by considering the theoretical implications of the results and advancing propositions to guide future criminological research on social engineering, fraud, and deception more generally.

Among hackers and information security practitioners, the manipulation of people through deceit to gain access to sensitive information or secure systems is often referred to as “social engineering” (Hadnagy, 2018; Mitnick & Simon, 2002).1 The term describes a constellation of deceptions used to compromise information security systems like “phishing” (email-based frauds), “smishing” (text-message-based frauds), “spear-phishing” (targeted email-based frauds), “vishing” (phone-based frauds), and in-person ruses.2 Estimates place losses from such frauds in the billions of dollars per annum (IC3, 2019, p. 20).3 Yet not all harms are economic as individual victims of social engineering and related frauds may experience significant emotional, psychological, physiological, and lifestyle damages (Cross, Dragiewicz, & Richards; Cross, Richards, & Smith, 2016; Whitty & Buchanan, 2016)

6. Conclusion

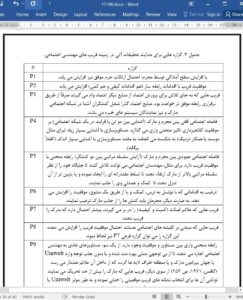

Synthesizing the results of this study indicate that social engineering deceptions are best understood as a performative, situational endeavors structured by interactional norms dictating social congress across hierarchically and vertically situated actors, the abstraction of trust under the expert systems of modernity, and proximity within social networks. In other words, deceptions are situations where the micro-interactional and the macro-structural interplay and co-mingle (Ferrell et al., 2015). Yet this is only one study of social engineering. Other studies may, of course, draw different conclusions. For this reason, this analysis advances testable propositions concerning factors that influence social engineering success drawing from the previously described themes and social theories. These propositions may be useful for criminologists and other social scientists interested in social engineering and related forms of deception (Table 3).