Abstract

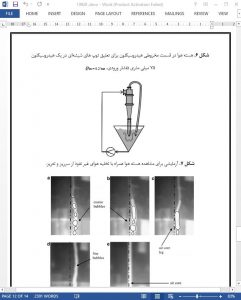

Air core formation has been investigated in hydrocyclones operated with clear water and a lucid suspension of glass balls. Hydrocyclones form a central air core which extends over the complete hydrocyclone length. Air is sucked in the core at the underflow discharge. The air core diameter can be determined balancing the positive pressure gradient and the centrifugal force in the rotational flow field. In dense flow separation (high feed solids content) the air core in the conical part of the hydrocyclone is suppressed. The hydrocyclone operates as it is air sealed because the solids are discharged trough the underflow as a rope. Then, air can be introduced to the hydrocyclone only on the feed side. In practice, feed suspension always contains more or less dissolved or dispersed air. Observations in a transparent hydrocyclone show that dissolved gas is released due to the pressure drop inside the hydrocyclone. The generated micro bubbles grow by coalescence and move in the centrifugal field toward the centre, where an air core is formed.

1. Introduction

Air is the often the neglected third phase of the 3-phase flow in the hydrocyclone. The air core at the center of the hydrocyclone is an unavoidable phenomenon in the rotational flow field which does not directly influence the classification process in the apparatus. However, this is different in new applications of the apparatus to flotation (Puget et al., 2004) and to separations in multi-phase systems involving vapors and gases (Madge et al., 2004) where the air core plays a more active role. Furthermore, the geometry and movement of the air core were identified as being sensitive indicators of the operational state of hydrocyclones (Neesse et al., 2004a,b,c). Therefore, in recent years studies on the air core in hydrocyclones have been the subject of intensive research. At present, the knowledge on air core behaviour is limited and based mostly on observations in transparent hydrocyclones (Ternovsky and Kutepov, 1994).

5. Conclusions

Geometry and movement of the air core are sensitive indicators of the operational state and can be used in hydrocyclone monitoring. The air core radius can be estimated based on the Navier–Stokes equations assuming the force equilibrium between pressure gradient and centrifugal force at the boundary liquid–gas. This physical consideration leads to Eq. (8) which indicates that the air core radius is primarily determined by the hydrocyclone geometry. Of practical interest is the question under which conditions the air core could be suppressed. According to Eq. (8) this can be obtained by increasing the pressure in the overflow. To note, the standard operating conditions are not taken in account here.