SUMMARY

Geopolitical research is frequently portrayed as a dead end. To some scholars it appears that in the 21st century geography is largely scenery, all but irrelevant to the most important issues of grand strategy.

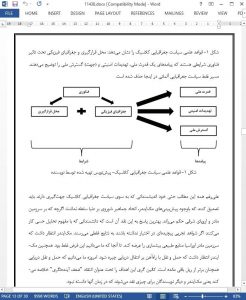

This working paper aims to revitalise geopolitics, reflecting both on the critique of the subject and the strengths that have characterised it for more than a century. It is argued that geographical conditions constitute a set of opportunities and constraints, a structure that is independent of agency. General patterns and long-term processes can be aptly explained by this structure but geopolitics is not a theory of state behaviour or foreign policy.

Understanding specific phenomena that occur in international relations therefore requires taking into consideration non-geographical factors. Such a combination of geographical and non-geographical factors provides sound explanations, as several examples demonstrate: China’s projection of power into the Indian Ocean, South Africa’s approach to the political crisis in Zimbabwe in 2008, Iran’s maritime strategy and the poor integration of Colombia and South America.

INTRODUCTION1

Nicholas Spykman once wrote that ‘ministers come and go, even dictators die, but mountain ranges stand unperturbed’.2 Due to their persistence, Spykman regarded geographical conditions – the physical reality that states face – as being decisive for international relations. This type of geopolitical thinking has been strongly criticised, more recently by constructivists such as John Agnew, Simon Dalby and Gearóid Ó Tuathail,3 and for decades by realists. In an article recently published in the journal Orbis, Christopher Fettweis argues that geopolitics suffers from major descriptive, prescriptive and predictive deficiencies. According to Fettweis, geopolitics is therefore unable to produce meaningful scholarly work.4 It has become obsolete, as he claims in an article published earlier in Comparative Strategy.5