Abstract

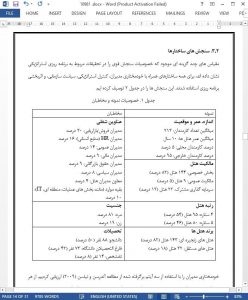

This article reports on the impact of managerial autonomy and strategic control on organizational politics and show how the latter influence effectiveness of strategic planning. In doing so, it outlines particular directions that a rebalanced strategic management research agenda may take. Whereas organizational politics have received sustained interest in the management literature, its conceptual and empirical examination in the tourism industry has been meagre. This study contributes to fill this gap by analyzing data from 175 four- and five-star hotels located in a less researched region, the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries. The findings indicate that high levels of autonomy combined with low levels of control negate the effectiveness of strategic planning by increasing organizational tensions. Drawing on political and organizational perspectives, an interpretation of the results and policy implications are discussed. The study also delineates interesting research avenues for further research on organizational politics in the tourism industry.

1. Introduction

A broad range of studies have conceptualized organizations as political coalitions of members with often divergent goals; and they have also attested to both the ubiquity of organizational politics and to their widespread destructive impact on organizational outcomes (Elbanna, 2010; Kacmar & Baron, 1999; Kreutzer, Walter, & Cardinal, 2014). However, with few and less related exceptions (e.g., Buonocore, 2010; Hung, Yeh, & Shih, 2012), there has been very little theoretical and empirical research on organizational politics in the hotel sector, despite its importance and its treatment for decades in the management literature. The research reported in this article aims to help to fill this gap by examining the impact of two antecedents of organizational politics (managers' autonomy and strategic control), and one of its outcomes (the effectiveness of strategic planning).

5.1. Implications for managers

A good understanding of political behavior could serve to forestall its harmful manifestations and instead use it to broaden discussion, in the best long-term interests of both people and organizations. For example, although it was argued that top executives should give middle managers more autonomy since it significantly contributes, for example, to developing their capabilities, top executives need to do so carefully because of the possible negative effect of autonomy on other organizational behaviors, such as organizational politics. Developing effective ways of managing autonomy, hence, could be useful for helping managers to take advantage of their autonomy in a way that contributes to the success of the organization rather than promoting politics (Alper, Tjosvold, & Law, 2000). In other words, autonomy is not simply giving managers the power to be self-directing; rather managers need to be prepared to effectively use autonomy when making decisions. For example, managers who rely on cooperation and the approaches of positive politics and constructive conflict (Alper et al., 2000; Kapoutsis, Elbanna, & Mellahi, 2014) would appear to be good candidates for the gift of autonomy, since it can be made to work effectively for the organization and themselves at the same time (Alper et al., 2000).