Abstract

Studies have reported that emotional facial expression recognition (EFER) may be altered in individuals with depression. This study examined EFER in adolescent girls with and without depression and further examined associations between relevant clinical features of depression and EFER. Fifty adolescent girls aged 12 to 19 years old meeting criteria for depression or subthreshold levels of symptomatology and 55 adolescent girls with no psychiatric diagnosis completed EFER tasks. Reaction time and accuracy for recognising expressions at high and low intensities, and sensitivity in recognising happiness, sadness, anger and fear were assessed. Data were analysed using linear mixed models. Adolescents with depression were marginally faster than those in the comparison group to recognize sadness, although this trend disappeared once covarying for age and antidepressant use. Amongst adolescents with depression, clinical features were associated with poorer EFER performance. In contrast, anxiety symptoms were linked to better accuracy and heightened sensitivity towards happiness. A better understanding of EFER in adolescent girls with and without depression, and how clinical features might be associated with altered patterns of EFER could help to explain clinical heterogeneity observed in such studies of adolescents with depression. Knowledge of socio-cognitive alterations associated with depression will help to better develop and tailor interventions.

1. Introduction

Depression is a leading cause of disability (Ferrari et al., 2013) and a common mental health problem experienced by adolescents worldwide (Lopez et al., 2006). Risk for the onset of depression increases significantly with puberty (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Adolescence represents a physical, psychological and social transition between childhood and adulthood and is a vulnerable period for the development of mental health problems such as depression (Blakemore, 2012; Vijayakumar et al., 2018). Following puberty, depression is more prevalent amongst women compared to men (Kuehner, 2017; Thapar et al., 2013). Prevalence of lifetime major depression is estimated at 12.8% in 15–24-year-old Canadian females (Statistics Canada, 2017), and up to 22.2% express subthreshold variants by the age of 20 years (Rohde et al., 2009).

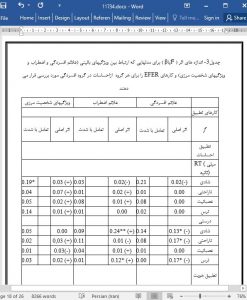

5. Conclusion

While group-based findings were not significant, our analyses focusing on adolescents with depression indicated that clinical features of severity of depression symptoms and borderline personality features were associated with poorer EFER performance. Symptoms of anxiety were however associated with increased accuracy and sensitivity towards happiness. A better understanding of both group differences in EFER and a more nuanced study of clinical features in relation to EFER in girls with depression could prove informative for clinicians. Knowledge on alterations in emotion-processing and how this relates to pertinent clinical features of depression could be important for identifying relevant intervention targets and tailoring treatment to individual needs.