Abstract

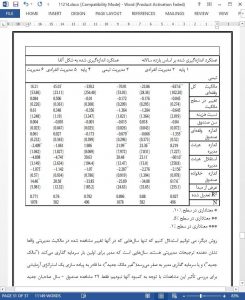

We examine the determinants of managerial investments in mutual funds and the subsequent impacts of these investments on fund performance. By using panel data we show that investment levels fluctuate within funds over time, contrary to the common assumption that cross-sectional data are representative. Managerial investments reflect personal portfolio considerations while also signaling incentive alignment with investors. The impact of managerial investment on performance varies by whether the fund is solo- or team-managed. Fund performance is higher for solo-managed funds and lower for team-managed funds when managers invest more. These results are consistent with the higher visibility of solo managers, and less extreme investment returns of team-managed funds. Our results suggest investors may not benefit from all managerial signals of incentive alignment as managerial investments also reflect personal portfolio considerations.

1. Introduction

Since March 2005 the SEC has required that mutual funds disclose annually the level of portfolio managers’ ownership in self-managed funds. Managerial investments may directly affect a fund’s performance through incentive alignment or career concerns, leading to a reduction in agency costs.1 When the SEC proposed this disclosure requirement, some fund managers argued that this information would be a noisy, non-informative signal that investors might have difficulty understanding. Although these disclosures began a decade ago, there have been few studies to date of the determinants of managerial ownership in self-managed funds and also the subsequent relationship between mutual fund performance and managerial ownership. Managers may invest in self-managed funds to signal incentive alignment with shareholders or to fulfill personal portfolio preferences. Managerial ownership in a self-managed fund may directly affect the fund’s performance if managers with more skin in the game invest more astutely, consistent with a reduction in agency costs (e.g., Jensen & Meckling, 1976; Mahoney, 2004). This governance view was cited by the SEC in 2004 in proposing and implementing the required disclosure of managerial investments.

5. Conclusion

We examine the determinants of managerial investments and subsequent performance consequences using panel data. This analysis uses data from a period when managers knew ex ante that their investments would be observed, and this may explain why our results both complement and diverge from the results of earlier papers. Chiefly, while Khorana et al. (2007) found managerial investments reflect personal portfolio concerns we find that managerial investments also signal incentive alignment, which is consistent with the Dimmock et al. (2011) argument that managerial investments are simply an asset within the manager’s personal portfolio. Next, while Khorana et al. (2007) and Evans (2008) found a positive relationship between fund performance and managerial investments, consistent with the incentive alignment hypothesis, we obtain evidence that this relationship depends critically upon the managerial structure of the fund. That is, solo and team managed funds respond very differently to managerial investments, with the effect positive at solo managed funds and negative at team managed funds due to the visibility and accountability of individual managers.